This post follows on from Out of the woods, pt 1.

The Australian bushfires fires of last summer feel like a lifetime ago now. I was lucky enough to live in a region that wasn't directly affected, although we were bordered by both the Currowan and Green Wattle Creek fires which devestated villages I know well. Relatives further down the coast lost their homes and were trapped for days. And all of us on the east coast spent months under more or less of a smoke haze, some days so strong it was hard to breathe. Residents of Canberra, a natural bowl, had the worst of it, but even in Sydney, the Opera House became invisible from across the harbour. For myself, I knew it was a bad day when I woke up and couldn't see Mount Keira three kilometres away. The anxiety was constant, and the relief of the drought-breaking rain in February was immeasurable.

What did the fire season mean for climate change? In the simplest terms - 830 million tonnes of carbon dioxide emitted. There are only five nations who emitted as much carbon as the fires into the atmosphere last year: China, the US, India, Russia and Japan. By far, they burnt the largest ever amount of temperate forests in Australia's historical record.

But the actual impact is a little more... well, hazy.

A word on the misdirections toward arson and backburning before I get into the science. NewsCorpse columnist Andrew Bolt was one of the many conservative commentators who tried to undermine the shift in consciousness that occured during the fires by blaming either deliberate arson or green tape preventing hazard reduction burning. They have been rebutted elsewhere in depth, so I won't spend this post explaining why they are wrong; however, for anyone who is interested in deliberately-lit fires, I recommend Chloe Hooper's book, the Arsonist, which details exactly what happened in one such case.

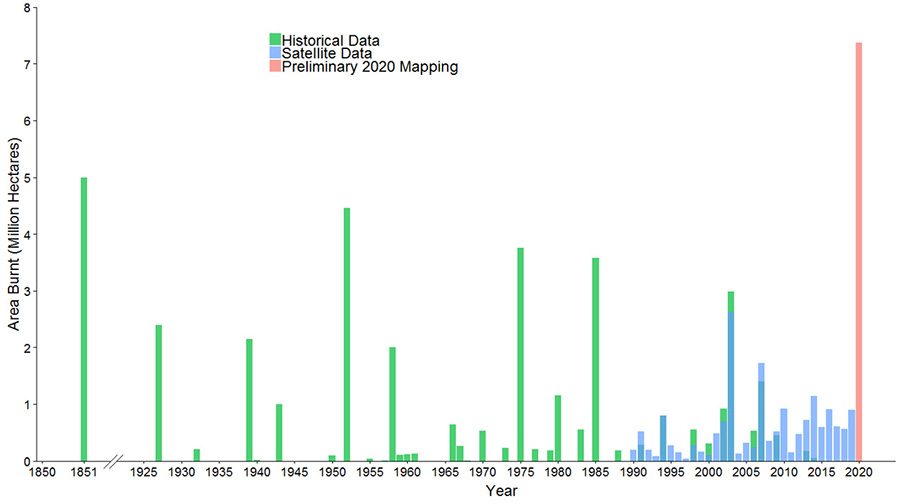

However, reading the technical update by the Department of Industry, Science, Energy and Resources (hardly a bastion of the culture wars) put Bolt's claims that the fires weren't the "largest" we've ever experienced to bed. The above graph, taken from that update, shows the devestation of temperate forests in Australia; savanna fires may cover far more area, but they represent far less destruction of endangered species, loss of habitat and biodiversity - and release of carbon emissions.

But what does the technical update have to say about the hundreds of millions of tonnes of carbon released into the atmosphere by the fires? In essence, that they don't count - at least not for our National Greenhouse Accounts or reporting to the IPCC. Most of the time, bushfires don't actually kill off trees in temperate Australian forests, only burn the bark, leaves and understory shrubs. As such, new growth will draw almost all the carbon released back out of the atmosphere within 10-15 years.

Is that really the case? Thankfully, we have had months of sustained rains in most of the coastal areas. They may have fallen down the page amidst the pandemic, but images of forests sprouting green new growth after the fire have done the rounds on Australian social media. The initial signs are good. However, it is only some kinds of trees which can regrow under such conditions. The fires burnt in rainforest areas previously thought safe, and may have wiped out many species.

It will take the forests a long time to draw down that much carbon, and in the short term, we are seeing a huge spike. During the fires, the British Met Office estimated we would hit a peak of 417 parts per million (PPM) of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere this year thanks to the fires. We have actually hit a recorded high of 418 on May 3rd. 450 PPM is almost certainly going to tip us over the line to a dangerous 2c of warming and runaway climate change, which I wrote a little about in this post.

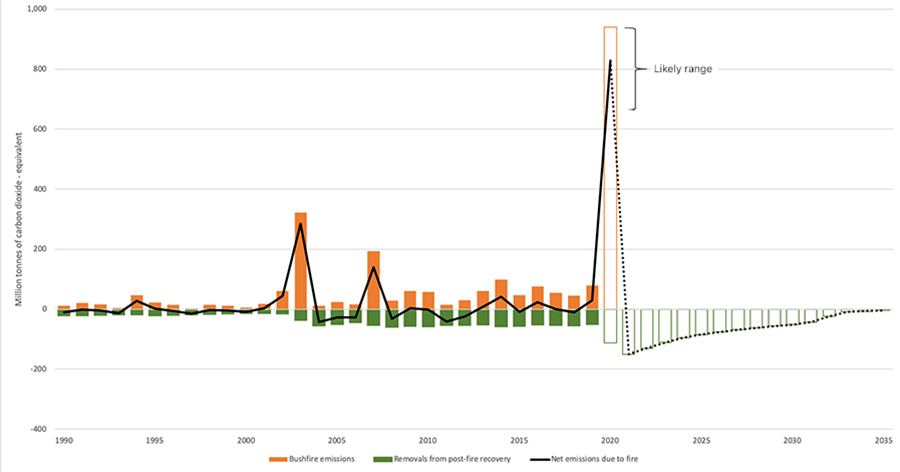

The spike will only go back down if the forests that burned are able to regrow for 10-15 years, without drought or future fires. This is almost guaranteed not to happen if we don't immediately address climate change, as this graph from the technical update hints. The negative green bars are showing the amount of carbon being drawn down by regrowth after fire, the orange the amount released. The more frequently severe bushfires occur, the less "carbon neutral" they become.

We must fight to protect forests in the wake of the fires. I will talk about the climate politics around forests in the final post of this series, but the most important thing to remark on here is to massively expand our bushfire fighting capacity. The priorities in Australia's bushfire fighting efforts were to protect lives first, property second, and forests third. We need to incorporate the urgent need to protect regrowing temperate forests from bushfires to maintain their status as carbon sinks, and intervene early.

That means more permanent volunteer payment provisions, and expanding equipment available to put fires out before they become too big to fight. In the fire season, aircraft and specialists had to be called in from overseas, and the state and federal governments all passed the buck on footing the bill. To buy C-130 waterbombers outright costs in the tens of millions of Australian dollars.

Celeste Barber's $51 million dollar Facebook fundraiser for the fires is a great step in the right direction, as the NSW Rural Fire Service must put the money towards equipment to expanding the Service's capacity to fight fires. It recieved over $100 million in donations throughout the crisis. Unfortunately, although Barber's fundraiser was clearly dedicated to the RFS trust, it's not exactly what people had in mind, as the description suggested it would help rebuild devestated communities - the RFS is currently exploring ways it can do both.

As runaway climate change becomes more and more inevitable, climate activists shouldn't only be fighting to "stop" climate change, but to fight for the greenhouse polluters to pay for the cost of defending communities from fires, drought and floods, and demand that they foot the bill when communities are destroyed. This call gained some traction during the bushfire crisis, but not enough. As with major devestating events in the past two decades, the job of rebuilding has largely been left to insurance companies, whose goal is to profit from the situation - by jacking up insurance premiums on the people most affected.

Which of these two responses plays out - the cost being placed on those responsible or those affected - will depend on the climate movement, and our ability to take up arguments around climate justice and bushfire justice. I will expand on that more in the last post in this series.

No comments:

Post a Comment